A day or two ago I saw a question pop up online, “Why does Pentecost only get one day to celebrate it?” The questioner went on to insinuate that the liturgical tradition has a bias against the Holy Spirit in favor of the person of Jesus, where there’s Holy Week and Eastertide and Ascension, on top of Christmastide and Epiphany. Apart from the obvious biblical and long-standing theological answer to why Christians give more overt attention to Jesus, let’s take a look today at the additional fact that Pentecost is not just one day, and never has been.

For well over a thousand years of Western liturgical tradition, most major holy days have what’s called an Octave: a period of eight days beginning on the holiday and running for a week after. The only octave tradition that directly impacts most Anglicans today is the All Saints’ Day Octave, wherein although All Saints’ Day is officially November 1st, the Sunday immediately following (within the Octave) is typically celebrated as All Saints’ Sunday. But back in the day, Easter had an Octave (which Prayer Book tradition has always observed in one way or another), the patronal feast of an individual church or diocese would have an Octave, and, among others, Pentecost had an Octave – from Sunday to Sunday ending with the feast of the Holy Trinity.

In current Roman Catholic practice that Octave has been suppressed, though there is the half-joking plan of priests celebrating Votive Masses of the Holy Spirit on the weekdays following Pentecost in order to simulate an Octave. In the Anglican Prayer Books we’ve never had instructions for a full Octave, but we have had special Collects and lessons for Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday.

Older prayer books call this holiday Whitsun or Whitsunday, modern prayer books call it Pentecost. The reason for the peculiarly English name of Whitsun is a story for another time – I’ll just link you to Wikipedia on that for now.

Whitsunday, the Day of Pentecost

The traditional Collect of the Day (which is the second listed in the 2019 Prayer Book for this day) is:

GOD, who as at this time didst teach the hearts of thy faithful people, by the sending to them the light of thy Holy Spirit: Grant us by the same Spirit to have a right judgement in all things, and evermore to rejoice in his holy comfort; through the merits of Christ Jesus our Saviour, who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the same Spirit, one God, world without end. Amen.

With this would be read Acts 2:1-11 and John 14:15-31 (omitting the last phrase “let us go hence.”). In the modern lectionary plan, part of Psalm 104 is added, and the OT and Epistle options are Genesis 11:1-9 and 1 Corinthians 12:4-13. It should be noted that, although the 2019 Prayer Book doesn’t specify this, the Acts reading ought to be read. The OT and Epistle lessons are both offered so that we have a choice of where to place the Acts reading. Precedent from Eastertide and the 1979 Prayer Book suggest that Acts 2 should be in the OT position, precedent from the next two days of the week suggest that Acts 2 should be in the Epistle position. So this is a legitimate choice; perhaps swap places every year so people hear all the potential readings most often!

Like Ascension Day, the 1662 Prayer Book appointed special Psalms for the Daily Office on Whitsunday: 48 and 68 in the morning, and 104 and 145 in the evening.

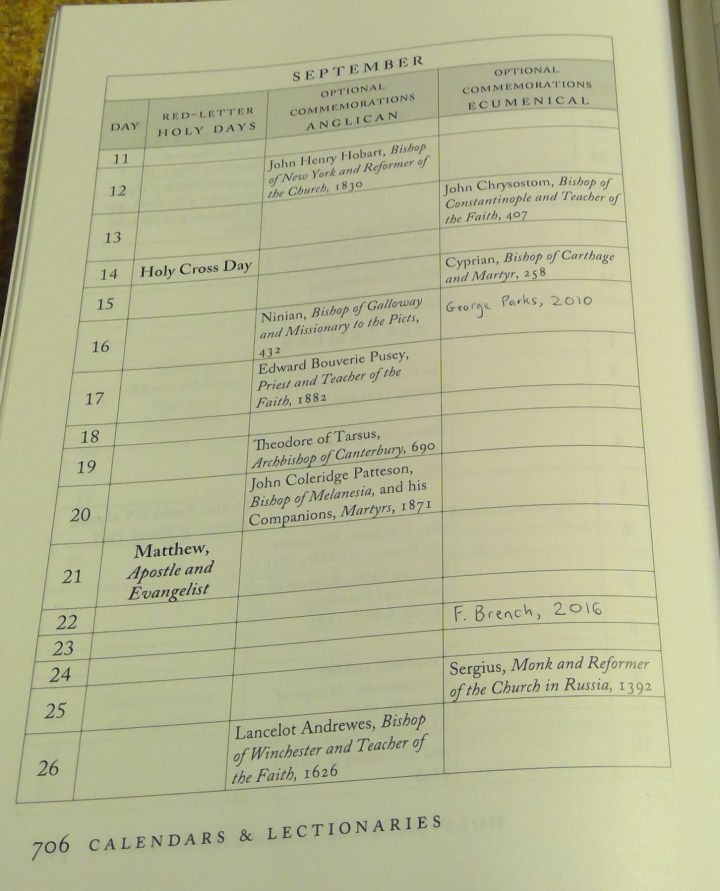

Unfortunately, according to the new prayer book (on page 614), “The Easter Season includes and ends with the Day of Pentecost. …The Collects, lessons, and prefaces for the Day of Pentecost and Trinity Sunday are not used on the following weekdays.” Previous drafts of our new prayer book included the traditional Monday and Tuesday of Pentecost, but they seem to have dropped away from the final edition. So it seems, at least officially, we in the ACNA are stuck in the same boat as the Romans, having to resort to appointing the “Various Occasion” propers “Of the Holy Spirit” on page 733 to fill out the old Pentecost Octave a little. Or you can just grab the following from classical Prayer Books:

Monday in Whitsun Week

The traditional readings were Acts 10:34-end and John 3:16-21; a proposed addition was Numbers 11:24-30 and Psalm 98. The 1928 Prayer Book added a new Collect:

Send, we beseech thee, Almighty God, thy Holy Spirit into our hearts, that he may direct and rule us according to thy will, comfort us in all our afflictions, defend us from all error, and lead us into all truth; through Jesus Christ our Lord…

Together, this day gives us a collection of further teachings about the ministry of the Holy Spirit along with another “pentecost moment” from the book of Acts.

Tuesday in Whitsun Week

The traditional readings were Acts 8:14-17 and John 10:1-10; a proposed addition was Ezekiel 37:1-14 and Psalm 98. The 1928 Prayer Book added a new Collect:

Grant, we beseech thee, merciful God, that thy Church, being gathered together in unity by thy Holy Spirit, may manifest thy power among all peoples, to the glory of thy Name; through Jesus Christ our Lord…

This day got a bit more specific about the work and power of the Spirit unite God’s people.

What about the rest of the week?

The Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday following Pentecost are Ember Days, which occur quarterly throughout the year, so they don’t get special Pentecost-featured propers. Some proposed Prayer Books (like the 2011 book) provide different Scripture readings for each of the Ember Days throughout the year, and thus provide the Pentecost Ember Days with a particularly Pentecost-appropriate theme regarding Spirit-empowered ministry. But sadly, no such option is available in the 2019 Prayer Book.

That leaves Thursday yet untouched. There is a small tradition of using that day to commemorate the Promulgation of the First Prayer Book, as Whitsunday 1549 was when the first Prayer Book was mandated to begin use across England. We’ll look at that some more on the day.

So yes, sadly, in a way Pentecost is kind of reduced to a single day in the modern calendar. But there is precedent in previous Prayer Books, both official and proposed, for the continued celebration of this great feast in various ways throughout the week.