In a couple days it’ll be the last Sunday before Lent begins. I have seen, and participated in, a couple different conversations about the liturgical color appropriate for that day, and so thought it prudent to compile the different perspectives and their major arguments

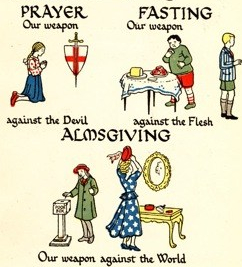

Before we begin, though, there’s a prologue question that should be addressed: “Who cares?” Granted, the Prayer Book tradition has never mandated a particular scheme for liturgical colors, and granted, the Puritan party of Reformers held the day for a while in Anglican practice whereby liturgical colors were not used by the majority of ministers. If that is the way you like it then there’s not a lot we can do for you here. The use of liturgical colors is one of the church’s many and ancient practices for providing visual aids to worship and teaching. As long as the colors are used in a consistent fashion, they can convey different postures and moods befitting different occasions. Black for mourning, white for joy, purple for penitence, and so on. But the key here is that these colors have to be used consistently with their use and meaning, otherwise they will only ever be fashion accessories and a frivolous game of ecclesiastical dress-up. That’s why getting the colors right, if you’re using them in the first place, matters.

The Traditional Option

If you’re using the historic calendar and lectionary, this Sunday is “Quinqagesima” – the last Sunday before Lent – and Western tradition is unanimously clear: the liturgical color is purple. The Pre-Lent season is nearing its end, Lent is almost here, the Alleluias have already been “buried”, there is no question: it’s purple. Easy! Done.

The Modern Calendar

Anglicanism has no history of its own when it comes to the liturgical color tradition; we’re just one of the several pieces of Western Catholicism in this matter. Therefore, when Anglicans switched to the modern calendar developed in the Roman Catholic Church, the standard color practice was also imitated. So if catholicity is your primary concern in choosing liturgical colors, or you’re just looking for the quick and easy answer, then do what the majority of Western tradition does in the modern calendar: it’s white. Done.

But, but, but…

Not everyone’s happy with this idea, though. Some argue for green, others for purple. So let’s look at these arguments and compare with them with the reasons for using white.

The argument for green stems largely from a concern for the integrity of the Calendar as a whole and a rejection of the way the Last Sunday after Epiphany is treated. This Sunday, wrapping up the modern Epiphany season, is always about the transfiguration of Jesus on the mountaintop. But, Green Advocates point out, the Transfiguration is already a feast day in the calendar: August 6th. To read it in the Gospel lesson this Sunday and wear white is basically to double that holy day in the calendar. This is an inappropriate imbalance, they say, and this Sunday should be normalized to green along with the rest of Epiphanytide.

The argument for purple is a sort of hybrid approach to the modern calendar, drawing in some of the mindset of the old. Instead of looking at it as the Last Sunday after Epiphany it’s the Last Sunday before Lent, and the very observance of Christ’s Transfiguration as a prelude to Christ’s Passion supports this case. This Sunday is basically the Pre-Lent Sunday of the modern calendar, and thus, in line with pre-1970’s liturgical practice, this Sunday is best characterized by purple.

So why does the Roman order (and all standard Protestant recommendations) appoint white for this day? Part of the answer is a liturgical symmetry: both of the green seasons (after Epiphany, after Trinity) begin and end with a white Sunday (1st after Epiphany, Last after Epiphany, Trinity Sunday, Christ the King Sunday). This may be rebutted by some: Christ the King Sunday shouldn’t be white either, and like the transfiguration is best left to its “proper” place in the calendar (Transfiguration to its feast on August 6th, Christ the King to its mini-season with Ascension Day and Sunday after). But, I would point out, these arguments to take white away from these Last Sundays at the end of the green seasons, especially to replace them with green, are also arguments against the very nature of those Sundays in the modern calendar. In short, a color scheme revision isn’t enough, these objections cut all the way to the lectionary, and will not be solved unless or until the lessons for “transfiguration” and “christ the king” Sundays are also changed.

Even the appeal for purple runs into trouble along similar lines. The argument for purple has the advantage of befitting the readings – especially now in Year C where the Epistle lesson happens also to be the traditional Epistle for Quinqagesima! – but still requires a slight re-write of the calendar. We have the Last Sunday after or of Epiphany, but purple requires the name to be Last Last Sunday before Lent. It is natural, in the liturgical context of the modern calendar, to reconsider this Sunday as a Pre-Lent purple sort of day, but you have to change its name in the Prayer Book in order to justify it fully.

The Saint Aelfric Customary’s Recommendation

I sympathize with all these arguments. It’s ecumenical to stick with the Roman order and wear white; it’s annoying to double a feast day like the Transfiguration; it would be nice to bring back some of the historic Pre-Lent purple.

The arguments for green, I think, run into too many counter-arguments that create even more tension within the calendar, and ultimately lead in a direction of a complete overhaul. I’m not opposed to a complete overhaul; for the most part I’d like to see the calendar restored to the way it was before the radical revisions of the 1960’s and 70’s. But changing this one Sunday from white to green isn’t really going to help us get there.

The idea of using purple in the modern calendar may primarily be my own imagination; I don’t remember if I’ve actually heard anyone else suggest it before. It’s less disruptive to the calendar’s color scheme as a whole than choosing green, but it’s still clearly against the spirit of the modern calendar.

So, honestly, I still think white is the way to go. It may not be the best solution, but at least let’s think of it this way: this is our last hurrah before Lent, let’s do our best to enjoy it and sing Alleluia before we bury it for six and half weeks.