Welcome to Saturday Book Review time! On most of the Saturdays this year we’re looking at a liturgy-related book noting (as applicable) its accessibility, devotional usefulness, and reference value. Or, how easy it is to read, the prayer life it engenders, and how much it can teach you.

The next few books we’re going to look at are from liturgical traditions other than our own. Obviously it is important to well-grounded in who we are and what we believe and where we stand, but it is also important to understand that we don’t stand in a vacuum, but as a part of the greater whole of Western Catholicism, and further, universal Christianity. So today we’re going to go with one of the more random entries on my liturgy shelf: the Saint Joseph Continuous Sunday Missal, from 1963.

As you probably know, the 1960’s was a hotbed of liturgical changes in the Roman Church, and the vast majority of the Protestant world was about to follow suit. The council known as Vatican II ran from 1962 to 1965, and one of its earliest reforms was for the liturgy in the local vernacular. This Sunday Missal from 1963 represents a brief slice of Roman liturgical reform where it’s all in English, but most of the “novus ordo” (new order) stuff hasn’t been introduced. It’s a precious snapshot of the Tridentine liturgy in English, something that’s almost completely lost today. Under Benedict XVI, Roman Catholics got their Latin Mass back, but I’m not sure they got back their historic liturgy in the English language. Their situation is something like Anglicans having to choose between the 1662 Prayer Book with zero changes and the 1979 Prayer Book – super traditional to the point of liturgical fetishism, or super modern to the ire of traditionalists everywhere.

So, apart from historical reference, in a tradition not even our own, what use is this book to an Anglican today? Well, if you’re one of those crypto-Papist versions of Anglo-Catholic, then I suppose this book is pretty close to your view of an ideal liturgy in English. It may help inform how you use the Anglican Missal, or whatever other Prayer Book supplement you prefer. But most of us, I hazard to say, are more interested in Anglican liturgy and spirituality; what does this Roman book have to offer?

When I spent three years with my church in the classical prayer book lectionary, I learned a lot about how the liturgy used to be structured. Remember that the historic Sunday Eucharistic lectionary has just two readings: an Epistle (usually) and a Gospel. The Prayer Book tradition appoints a Collect for each Sunday and Holy Day to go with those two readings, but that’s it. But what I eventually discovered was that there are more “propers” to draw upon if one so chooses. There’s also the Introit and the Gradual – short pieces, usually chanted, usually from the Psalms, that are said near the start of the liturgy and between the Epistle and Gospel, respectively. But what are those texts, and how are they used? That’s where this book came in handy for me: by spelling out the full text of the Roman Mass for each Sunday of the year, it showed me how they did the Introit and Gradual, giving me insight into how those two additional propers could be put into the our liturgy.

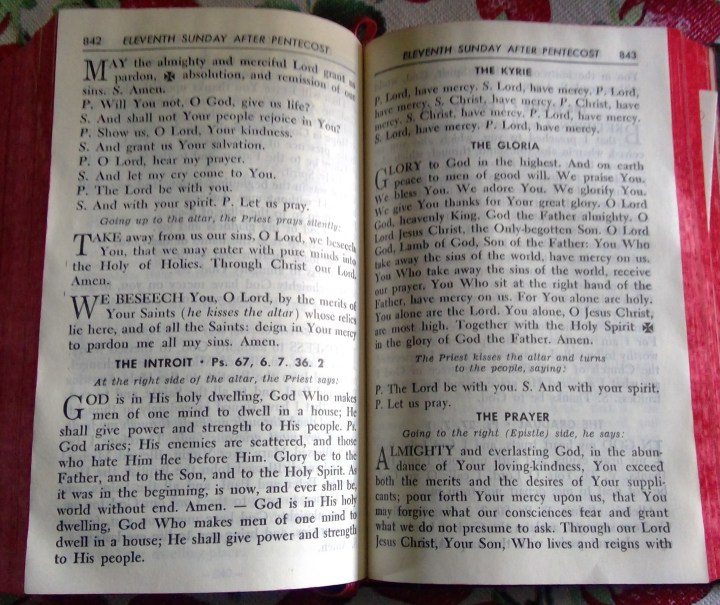

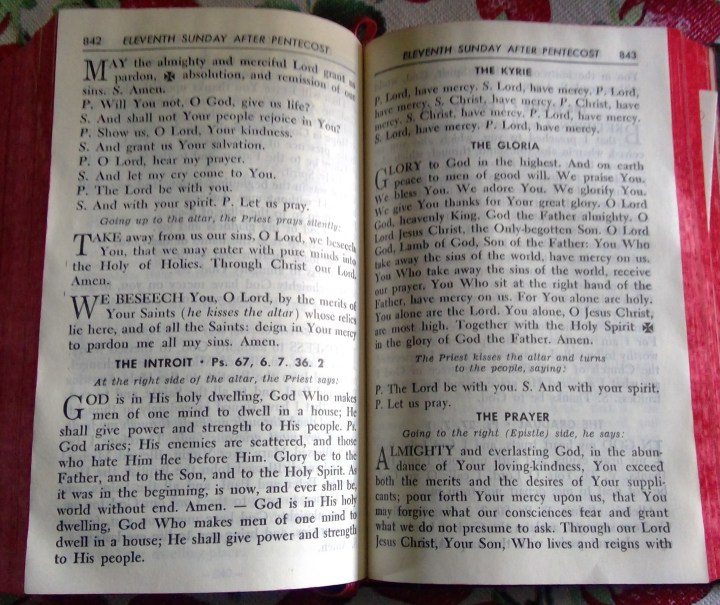

First you can see the Introit, between the “Foremass” confession and the Kyrie, functioning in essentially the same way as our Opening Acclamation today.

After the Kyrie and Gloria comes their Collect of the Day, and then we turn the page to find the Epistle, Gradual, and Gospel. Notice how both the Introit and Gradual use an Antiphon-Verse-Antiphon pattern, though slightly differently. The Gradual functions similarly to our (responsory) Psalm in modern liturgy.

Then we get through the Creed, Sermon, and arrive at the Offertory. It’s interesting to note that they appointed particular Offertory Sentences to particular Sundays, whereas the Prayer Book tradition just throws a 2-3 page list at you to choose from.

And then finally, after 8 pages of Communion prayers, we get to an oft-overlooked piece of liturgy, the Communion Sentence. As far as I’ve noticed, the Prayer Book tradition has always authorized this little piece of liturgy, but seldom (if ever) gave instructions on how to do it. Notice here that it’s said after the sacrament has been distributed and the vessels cleaned.

The Post-Communion Prayer follows the Communion Sentence – it’s almost as if that little Scripture verse is there to re-direct everyone’s attention to the reception of the Sacrament after the sometimes-lengthy process of communicating everyone, getting everyone back on track to pray the Post-Communion together.

I share this in detail partly because I think it’s interesting, but also because it sheds some slight on how certain elements of our own liturgy, old and new, work in similar tradition to our own. For example, I’ve only ever heard a Communion Sentence uttered at one church I’ve visited, and only tried saying one myself at my church once or twice. Perhaps old resources like this one can inspire us to look at our own liturgy with fresh eyes.

The ratings in short:

Accessibility: 5/5

If this book represented the way a church worships today, it would be incredibly useful. It’s easy to follow, the whole Mass through. It’s got a picture at the beginning of each Sunday Mass to give a visual sense of the day’s theme. Everything is clearly labeled. The book is long (over 1,000 pages) but not large. It’s got explanations of the calendar and the parts of the Mass, with color pictures, at the beginning. The whole point of this book was to help church-goers follow and understand the Roman Mass easily.

Devotional Usefulness: 1/5

As noted previously, this book represents a form of the liturgy that probably doesn’t exist anywhere anymore. And it’s very Roman, so the theological content of its eucharistic prayers is not entirely agreeable with the Prayer Book tradition. And although it does have some other prayer resources in the back, this book just isn’t really “for us”.

Reference Value: 3/5

If you’re interested in how various elements of traditional Western liturgy can/did/”should” look in English, this book, or another like it, is extremely handy. Its usefulness is pretty narrow, though.

If you chance upon a book like this at a yard sale or an estate sale, like I did, it’s totally worth shelling $5 to save it from the rubbish heap. It’s a book cool to explore, and it looks really pretty on your shelf, too! There’s a lot to be said for elegant, simple, beauty.